A conversation with Françoise Mouly, art editor at The New Yorker, curator of the 2025 exhibition at L’Alliance New York: Covering The New Yorker. Find a virtual visit of the exhibition & links to all the artworks mentioned in this post at the end.

Françoise Mouly is possibly the most New Yorker-esque of all French women. Rightly so.

Since The New Yorker was founded 100 years ago, she has served as its fourth art editor, a position she has held for more than three decades. Every week, she selects an illustration worthy of the magazine’s legendary cover, a position that has always been central to its identity.

In the first cover of The New Yorker, dated February 21, 1925, Rea Irvin, the distant predecessor of Françoise Mouly, depicted a dandy, later named Eustace Tilley, peering at a butterfly through his monocle—inspired by the early 19th-century Count d’Orsay, the incarnation of a dandy in the Encyclopedia Britannica of the time. This whimsical image played like a musical note, the first in a never-ending media and artistic score that the magazine has composed since then.

Many artists, famous and not, have illustrated the cover of The New Yorker. Among them were David Hockney, J.J. Sempé, Saul Steinberg, or Amy Sherald. But the process is the same for each one, famous or not: the artist submits an image, and Françoise Mouly, in collaboration with the editor David Remnick, selects the one that will become a snapshot of the magazine’s voice for that week.

The cover of The New Yorker is a cultural and editorial marker, one that Françoise Mouly has helped shape for decades.

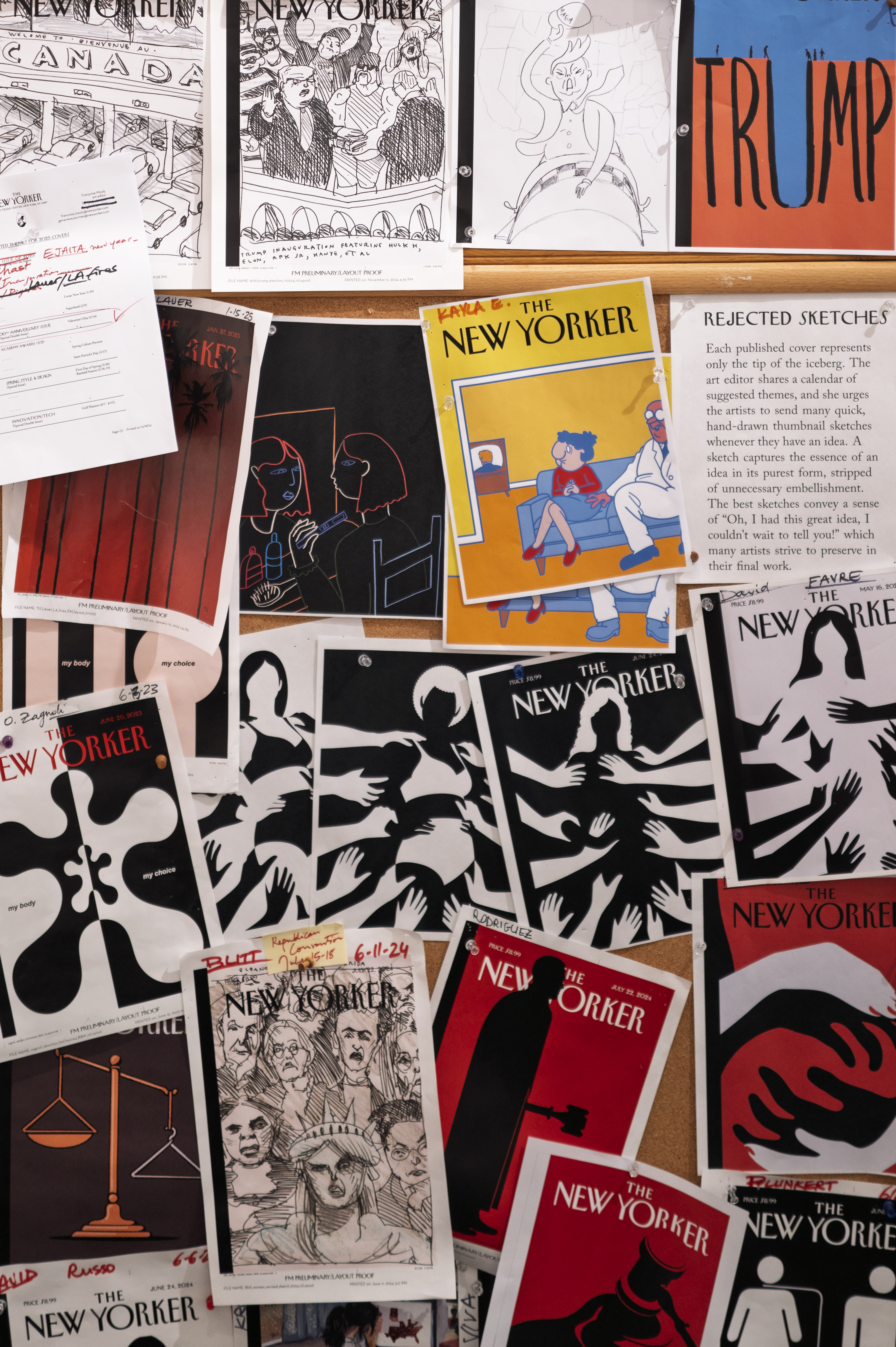

As she sat on a sofa at the entrance of L’Alliance New York for a conversation on the creative process behind The New Yorker covers, the adjacent gallery presented an exclusive series of artworks to celebrate the magazine’s milestone. Some became iconic New Yorker front pages—such as Maira Kalman’s Dog Reads Book or Ana Juan’s Solidarité, published after the 2015 Charlie Hebdo shooting in Paris, France—while others were never published.

One of the artworks exhibited at L’Alliance New York stands possibly among the most significant illustrations Françoise Mouly worked on. She published it soon after the 9/11 attacks. That morning, she was first and foremost a New York mother of two, not thinking about how the tragic news might impact her role as art editor at The New Yorker.

“September 11, 2001, is the day I learned to trust my own emotions,” Mouly reflects.

It was a Tuesday, New York City’s mayoral election day. Françoise was walking up Greene Street in SoHo ready to go vote with her husband, graphic novelist and author of Maus Art Spiegelman, when she heard the roar of a plane flying at low altitude and saw its tail crash into the North Tower of the World Trade Center.

“I first called my boss to do my duty as a journalist. Then Art wanted to turn back to follow the news on TV. I was screaming his name, ‘Art, Art,’ and thought others would take pictures. It wasn’t my problem. What motivated me was going there fast because my 14-year-old daughter had just started school at Stuyvesant High School,” a short walk away from the doomed towers.

Françoise, having studied architecture, immediately feared debris might fall on the school. On that bright, soft, and calm summery morning, she and her husband raced through the streets amidst the blaring emergency vehicles. In the chaos, they were the only parents who managed to enter the school before it was locked down.

“We spent an hour, maybe an hour and a half trying to find out where my daughter was; 10,000 kids had just started school, and the administration didn’t know what to do. They made an announcement asking students to stay in their classrooms, awaiting instructions from the Department of Education. I also wanted to take one or two of my daughter’s friends with me.” But the school refused unless there was a parental faxed permission, and no communication was getting through. “We managed to find our daughter but not before there was a kind of earthquake, and all the computers, all the lights went out. It was the first tower collapsing. I didn’t know that. All I could think of was getting my daughter out of there.”

As soon as they stepped outside, they watched the second tower collapsing in a thunderous crash of metal and broken glass. “We were surrounded by dust and people covered in white, running north, screaming. My daughter, my husband, and I were stunned, not understanding what was happening. Art had heard on the janitor’s radio that it was a terrorist thing and that something had also happened in Washington; he was starting to understand.”

At that point, Françoise’s only thought was now to find her son, a student at UNIS, the United Nations International School, on 25th Street and FDR Drive, less than 20 blocks south of the United Nations building.

That’s when her assistant contacted her: ‘Your office called. They want a cover.’

“My reaction was totally instinctive: anything but that. I couldn’t put on my professional hat,” Françoise recalls. “I went to get my son, and then I spoke to another mother, explaining that I had to go to my office because I had to make a magazine cover. This woman—who had just gone through the same experience—stared at me:

‘No cover’ she told me. ‘Just make the cover black.’”

JC Agid: So, you are now reunited with your two children and have this woman’s idea in mind. Just blackness. A hollow, black cover. How did you come up with the final result?

Françoise Mouly: My husband was drawing an image. Other artists were also drawing images. And honestly, I had seen what Art was doing, and two or three proposals, and nothing came close to matching what was happening. Yet, I had to show them to David Remnick.

The next day, I biked to the office, first stopping by my husband’s studio to pick up his CD. Art came down to the street, and I told him I thought we should go with a black cover.

‘Then consider black on black,’ Art told his wife. ‘You could draw the towers, black on black.’

Art Spiegelman to Françoise Mouly, September 11, 2001

Sitting in front of my computer, I realized this was the only possible response at that moment: an image that denies the image yet still carries the power of art to evoke that moment.

The shadowed style of the cover published after Donald Trump’s victory in the U.S. Presidential election in the November 18, 2024 issue seems to echo the one created after the September 11 attacks, doesn’t it?

The two are connected.

Did you have a piece ready in case of a Donald Trump victory?

No, no, no… I was asked by my boss. He had prepared the rest of the magazine for both scenarios—A and B. David asked me the week before, then again during the weekend, and each day before what was the plan B. I showed him some images, but I was not convinced by any of them. One of my plan B was to do nothing.

Meaning, absolutely nothing, a blank cover?

I proposed publishing a traditional autumn cover. He said, ‘No, that’s not a good plan.’ I showed him images that some artists had sent, but I hadn’t reached out to many people. I hadn’t had conversations with them because I don’t like asking artists, ‘Imagine how you’d feel if this or that happens.’

To be somewhat prepared but without presuming the final outcome.

I have a perfect example of waiting until the last moment: it was the election of Barack Obama. I hadn’t prepared a cover, unlike other magazines, because we didn’t dare believe it. Obama’s election had been so tumultuous; it was miraculous. That night, I received something quickly done by

Bob Staake—an image of Lincoln’s Tomb with the moon above it, figuring as the “O” of Obama. For the American eye, it was a historic moment. Moreover, Martin Luther King Jr. gave his speech at the Lincoln Tomb. Every American knows that. It was perfect—it captured the astonishment, joy, and surprise of all Americans, not just those who voted for Obama.

The first African American elected President of the United States: a historic election…

…that wasn’t contested, even from the other side.

There was respect between John McCain and Barack Obama.

Yes, even McCain’s supporters understood that Obama’s election was historic. In my office, I was told, “It’s fantastic: all the newstand copies sold out.”

Ten weeks later in January, I was then asked to create a poster for the inauguration. I suggested the Lincoln’s tomb.

“We want a new image,” I was told.

“You don’t understand: this image corresponds to a lived moment. Everyone wants it because we will remember how we felts when we heard the news.”

“No, no, no,” they said. “We need a new image for the inauguration,” so I did.

We published a cover showing Barack Obama in the guise of George Washington. But the image represented nothing. It was manufactured.

Yet, it did represent the news, didn’t it?

It was no longer the artist’s emotion—it was the editors’ decision. It was all wrong and upside down—me asking an artist to draw a portrait of Obama that would represent the emotion we might feel at his inauguration. It was anticipating that moment.

Which should be avoided?

You shouldn’t do that. It deprives you of truly feeling things.

Last November, it worked out well… because you had not anticipated Donald Trump’s victory.

No. So, I called an artist I work with often, Barry Blitt, and asked him to quickly rework a sketch. ‘But do it very fast and very small; I want to enlarge it, and I want it to have a feeling of vomiting. I want this drawing now—no half hour, no hour-long wait. It’s 9:40 p.m. on election night. The result hadn’t been confirmed yet, but we could publish it the following morning.

A sketch made on the fly!

I told Blitt, ‘I want it to be an ink stain. I want it to look like it was made very quickly, in a rush.’

The speed of execution is very important. This is where the artist’s hand matters.

at L’Alliance New York

For Kamala Harris, though, one of your artists, Kadir Nelson, had prepared a massive oil painting. It was a centerpiece of this 100-year-anniversary exhibition at L’Alliance New York. Kamala Harris wears a blue outfit adorned with portraits of individuals who advanced civil rights and the Democratic Party, including James Baldwin, Nina Simone, Barack Obama, and Joe Biden. This work was slated to be on the cover of The New Yorker if Kamala Harris had won the White House in November 2024.

Who is Kadir Nelson, the artist of this unpublished painting?

I’ve known Kadir Nelson since his studies at Pratt, the School of Art. Someone told me I had to check out his work. He created background drawings for Steven Spielberg’s film Amistad, drawings meant to express emotions, almost like stage settings. They were extraordinary. I went to see my editor, Tina Brown, and I had to negotiate with Spielberg’s team to show the behind-the-scenes work, but it made me aware of his work. Nothing really happened after that until David Remnick spoke to me about Nelson Mandela: ‘He’s not getting any younger, and I want us to be ready. Can you request some drawings?’ David asked me. Typically, we don’t prepare obituaries, or else end up doing them all the time. This time, I broke my own rule, the one about usually asking for ideas from multiple artists. I asked just one person.

Kadir Nelson.

It was Kadir, and that started a long collaboration. It’s really a conversation with the artist where he suggests subjects to me. For instance, Kadir proposed an image of himself on the beach—it became a viral image of a Black man wearing shades, standing proudly with his children by his side. Why? There are very few images of Black men as fathers. It took on a whole different dimension. And the pride with which this man stands, his gesture with his children, protective of them, the whole reality of this image of a proud dad on the beach made it the perfect summer picture. It wasn’t as if the art director was imposing a subject on the artist, but the artist must feel encouraged to propose an image corresponding to his reality.

Did you ask Kadir only for an image of Kamala Harris?

For Kamala, many artists submitted images. There was really a moment in August when she was officially nominated when we thought there was a good chance she’d be elected. I was receiving many images, but we had to keep one of the best for the moment she would be elected.

Kadir Nelson didn’t want to just create a drawing; he envisioned a painting.

David Remnick knows this too. When talking to an artist who does oil paintings and wants to produce something historic, you can’t just do it the night before and make a quick sketch. So, we had to plan ahead, but that’s the flip side. These are conversations with artists I know well. They know how we work. I ask them to send me their ideas without worrying about whether they would be accepted or not.

I’ve been at The New Yorker for over 32 years, and each year, I introduce new artists.

Françoise Mouly

A great deal of freedom and uncertainty.

Often, artists ask me if I need an image on a specific subject. My answer is always, ‘Don’t ask me the question; if you have an idea, just send it to me. Maybe I won’t need it, but if it’s a good idea, it will become a cover.’

The subject was clear here: to illustrate Kamala Harris, who could have potentially become the first female President of the United States.

It’s not easy to create a portrait that will appear with words. Here, it wasn’t just about depicting Kamala Harris but also saying something about her.

Did you know that Kadir Nelson would incorporate many other stories within the painting?

Kadir is the one who chooses the style.

This isn’t the first time he’s approached a figure by incorporating other portraits into their clothing.

He had already used this style for a portrait of Martin Luther King Jr. It was his personal response to explain that there was a historical precedent. He used the same approach in the oil painting of George Floyd: Say Their Names, which is also part of the exhibition. In George Floyd’s portrait, he painted many others who were killed by police as well as anonymous slaves. He depicted Trayvon Martin, Breonna Taylor, so many victims of racist violence, about 30 to 40 other Black individuals.

Is this the first time you have considered a cover for a female Commander-in-Chief of the United States?

No, no, no, no… you’re twisting all the knives in all the wounds. I did something similar with a proposal by Malika Favre in 1996.

Madam President!

Yes. Malika sent a sublime image of a woman turned towards a window with the moon, and it represented not just what had led to that moment but the starting point of what was to come. We believed there was an 85% chance it would be Hillary, but the American electoral system is so unrepresentative.

What you mean is that Hillary Clinton had won the popular vote.

Yes, by 3 million votes.

So, your job is also to translate current events through an artistic lens, without ever taking a stance on the editorial content, and then determine what makes the cover while creating surprise.

There is a distinction between the worlds of commercial and artistic art. In the world of Art with a capital A, the artists decide what they want to paint. It’s neither the gallerist nor the public—it’s for themselves, to express their innermost feelings. In commercial art, the goal is to sell a magazine or illustrate a story or special issue. Often, the image serves a purpose set by someone other than the artist, and the final image is chosen by an editorial committee.

The New Yorker doesn’t fall in either categories.

We have extraordinary privileges. The artists are the ones who contribute to the subject; we don’t have to publish about an event unless we have something to say. There are many topics for which we’ve received sketches, and we haven’t published a single one. The periodical nature of the magazine means we accompany the reader all the time—during quiet moments, during tough times—and issues pile up by the bedside. The same rule applies to the content inside: it’s only there if it’s good and adds to the cultural dialog. The cover sets the tone, but the article published last week will be just as interesting and well-written in six months or three years.

However, as we speak, the next cover will focus on a current topic: the fires in Los Angeles. Who decides on this—just you, or do you and David Remnick make the choice together?

It’s very simple: I had a cover in place for the current issue, and when I went to see David last week, I showed him proposals I had received about the fires in California. This climate change disaster is ongoing, daily, but not always as visual and dramatic.

I asked David, ‘Do you think we can make this the cover?’ We couldn’t go with it this week because we had already approved an image ahead of the presidential inauguration. The week after, we both hesitated. Would the fires still be relevant next week? Neither of us were sure.

‘I’m going to prepare two covers, and you can decide on Thursday,’ I told him.

David came to see me before the Thursday deadline and said, ‘Listen, I just spent an hour on the phone with a writer from California who lost her house. It’s an immense tragedy. Let’s do it, let’s do the fires.’

You’re not just an art director; there’s a very journalistic side to your work.

I react to the person making the call. It’s their decision. When Tina hired me…

… Tina Brown, who hired you in 1993.

Tina arrived in 1992 and hired me in 1993. Her first issue, on October 5, 1992, featured an Edward Sorel cover to announce her arrival. When she hired me, there was a lot of work to be done in reorienting the mission of The New Yorker. It had become a sort of sacred temple, defined only be what William Shawn (Editor from 1952 to 1987) wanted it to be during his years. The New Yorker staff was still trying to make the great years of William Shawn, the 1950s and 60s, live on.

William Shawn had an attitude towards the covers and wanted them to offer solace in relation to everything happening in the world. He certainly didn’t want them to have anything to do with the content inside or the daily events. For 30 or 40 years, he, of course, published fantastic images by Saul Steinberg but also many predictable covers. Every week, you would see a picturesque bridge in Connecticut, a bucolic scene, or something sentimental about New York.

If you didn’t know which artist it would be, you could predict that in spring, you’d see spring-like images, and in summer, summery ones. My predecessor would send eight covers to the printer in June, and they would be on vacation all summer.

That’s impossible under the current leadership!

Oh no. With David Remnick, that’s not possible.

My job was to completely change that, but I didn’t want to impose another house style. It’s not easy to put something out every week and still maintain that element of surprise.

Without relying on a fixed style?

Yes, without a fixed style, without a team of artists decided in advance. They’re not always the same artists.

You work with great artists and illustrators, but are you always looking for new ones?

I’ve been here for over 32 years, and each year, I introduce new artists.

It seems to bring you real pleasure. Is that your definition of success?

It’s the only success that matters. You don’t know, and I don’t know who will be on the cover next week.

We do know that sales have doubled since you joined The New Yorker in 1993.

That’s thanks to the editors-in-chief I have worked with.

Doesn’t the cover remain the image that seduces, attracts, and entices readers to buy the magazine?

That’s very kind and flattering, but I have only implemented the editorial vision first of Tina Brown and then of David Remnick, embodying—I’m happy to take credit for this—the beauty of The New Yorker over the past 32 years.

I sold cigarettes at Grand Central. I was an actress in a play by Richard Foreman. I made models in an architecture agency. I worked in construction painting, and I was an apprentice plumber and electrician. I loved that period. It was fantastic—anything felt possible.

Françoise Mouly

Françoise, while your name is associated with The New Yorker, you’re a New Yorker. When you arrived in New York, at the age of…?

At the age of 18.

It was a city in ruins at the time.

(Laughs) That’s not how I perceived it.

A city on the brink of bankruptcy.

It’s New York in the 1970s—the cinematic city of Robert De Niro and Taxi Driver.

You arrived with your hands in your pockets, leaving France behind, your architecture studies, a family, and a sense of comfort that lay ahead. It’s hard then to project yourself to 1993, let alone to 2025 when The New Yorker celebrates its 100th anniversary. You started from scratch, working as a saleswoman in New York.

I sold cigarettes at Grand Central. I was an actress in a play by Richard Foreman. I made models in an architecture agency. I worked in construction painting, and I was an apprentice plumber and electrician. I loved that period. It was fantastic—anything felt possible. In New York, people were open to being asked questions. I learned how to ask them—something you don’t learn in France, where you are taught to pretend to know everything. This is completely useless; it prevents you from being naïve, from not knowing and asking. In New York, people were eager to explain what they were doing, letting me discover something. It’s wonderful to be ignorant. In France, you’re not allowed to say you are ignorant or be ignorant.

To pursue knowledge, you first must accept your ignorance.

That’s what I discovered.

How did you meet your future husband, Art Spiegelman, and get involved with him in the world of drawings?

I discovered him through his work a few years after arriving in New York. I was thirsty for comics because I still didn’t speak English well.

Are you saying that you learned English with Marvel’s Spider-Man?

At first, a friend advised me to buy the Sunday New York Times. And three and a half months later, I was still bent over it, not understanding a thing. I didn’t know you were supposed to choose sections. I started at page 1 and tried to read the whole thing—until I realized it wasn’t feasible. Since the Sunday newspaper wasn’t working, I turned to comics, as that’s the language as it is spoken.

Not speaking English was even more frustrating since I had scored 18/20 in English in France (note: A+). It taught me to be quiet, which was already a very good thing. As a good little French girl, I had an opinion on everything, even though I knew nothing. It taught me to listen, a valuable lesson, especially at that age. I learned to ask naïve questions. And to be honest, I am naïve—I had the right to be. I came from nowhere. I was open to all possibilities.

And then comes the encounter with Art Spiegelman!

At the time, Art lived in California. He had created a comic magazine called Arcade. That, I could read. It spoke to me. We had mutual friends who were independent filmmakers—it was also a visual culture. I was learning to be quiet and watch.

When I read Art’s comic about his mother’s—The Prisoner on the Hell Planet—I was astonished that someone could do something so private in public and that I could experience such intimacy with someone through paper. It felt like reading a book, but even more visceral.

I knew Art socially, I called him, asked questions, and we stayed on the phone for eight hours—me, who hated speaking English, especially over the phone when I couldn’t read lips or body expressions! That’s how we met. Art asked me:

‘What are you doing for Thanksgiving?’

‘Thanksgiving, what’s that?’ I replied.

‘Oh! It’s the tradition when you go to Chinatown and eat turkey,’ he told me.

Now, Thanksgiving is our family’s preferred tradition.

Art Spiegelman, the American cultural connection!

Art taught me a whole bunch of English words. He was a big fan and friend of Philippe K. Dick. During my early years, I would use terms like ‘conapt’ and ‘rushmore effect,’—concepts and words that were part of his vocabulary, although they didn’t exist in English and actually came from the imagination of Philip K. Dick.

The word ‘intimacy’ you just used captures quite well with the emotion, originality, and surprise that each New Yorker cover evokes. These illustrations allow the artists to express something deeply personal.

Very personal and shared publicly on the cover of the magazine. Each drawing is signed. That’s important to me. I handle the layout and framing, ensuring there’s always the artist’s signature on the cover. Every cover is a personal work of art.

If there is an artist from the past you wish you could have worked with, who would it be?

When I worked with Saul Steinberg as his editor, I learned so much from him. He was friends with a whole bunch of other writers, and he once told me:

‘When you go to Paris, I’d like you to meet my friend Henri Cartier-Bresson.’

I couldn’t do it because I had ten thousand other things to do… (silence) and I regret it.

Cartier-Bresson, a photographer!

Yes! Recently, I saw an exhibition in Paris about surrealism, and I passed by Cartier-Bresson’s photographs in the hallway. I thought, ‘Aie, aie, aie. Why didn’t I immediately stop everything!’ I didn’t realize that time waits for no one—that people don’t wait. I regret not taking that opportunity.

It’s always hard to admit that we often have more time than we think to meet others another day.

Yes, but now, I pay attention. I seize the opportunity.

Kneeling from left to right: ?, Françoise Mouly, Tatyana Franck and Rodolphe Lachat (co-curator of the exhibition), Gayle Kabaker

Opening night of Uncovering The New Yorker, L’Alliance New York | January 2025

All pictures in this post (c) JC Agid – link to website

New Yorker Links on some of the covers mentioned

in this post:

Eustace Tilley by Rea Irvin

Dogs Read Book by Maira Kalman

Solidarité by Ana Juan

9/11 by Françoise Mouly and Art Spiegelman

Reflection by Bob Staake

Obama by Drew Friedman

Nelson Mandela, Hero by Kadir Nelson

A Day at the Beach by Kadir Nelson

Say Their Names by Kadir Nelson

After Dr. King by Kadir Nelson

Madam President: The Cover that Never Was by Kadir Nelson

If Hillary Had Won by Malika Favre

Two’s a Crowd by Barry Blitt

Flames and Shadow by Till Lauer

Issue of October 5, 1992, by Edward Sorel

Revisit virtually L’Alliance New York exhibition : Covering The New Yorker, curated by Françoise Mouly and co-curated by Rodolphe Lachat. All Artworks: copyright belongs to the artists.

Frames and vinyl production by Picto New York | Julien Alamo https://www.pictony.com

Leave a Reply